Summary #2 of SESSION 1 – URBANITY, WELLBEING AND EQUITY

Focus on the urgent need for better and more affordable housing in rapidly growing cities and areas of crises.

Margaret Donnelly Moran is the Deputy Executive Director for Development at the Cambridge Housing Authority in Massachusetts.

NAHRO (National Association of Housing and Redevelopment Officials) focuses on promoting affordable housing, community development, and urban revitalization. It supports policy advocacy, professional development, ethical standards, and diversity, equity, and inclusion in creating strong and sustainable communities.

oOo

Cambridge – Public Sector Developments in one of the most expensive regions of the United States

Margaret speaks. “It’s a difficult exercise after the previous intervention, but I would like to sincerely thank Hussam for his hopeful words and for the love he has for his land. We all want to do our part to support the rebuilding and restoration of your communities.”

I’m Margaret Donnelly Moran, Deputy Executive Director for Development at Cambridge Housing Authority, and Matthew Pike, our Director of Strategic Initiatives, is with me today. I have been with the Housing Authority for over forty years and have led reinvestment and expansion efforts for the past twenty-five years.

Introduction

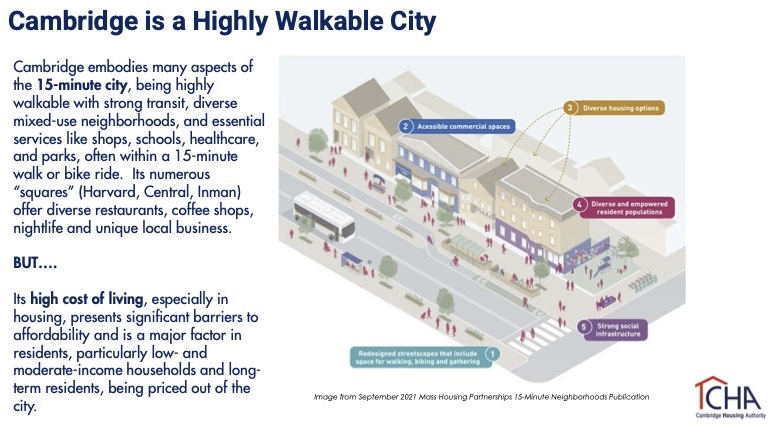

Cambridge embodies many of the core principles of the 15-minute city and INTA’s culture of urban health. The city is highly walkable, supported by strong public transit, and shaped by dense, mixed-use neighbourhoods where essential daily needs — such as shopping, schools, health care, and parks — are typically accessible within 15 minutes on foot or by bike.

Our presentation focuses on how a public sector agency has adapted in one of the most expensive housing markets in the United States.

Presentation

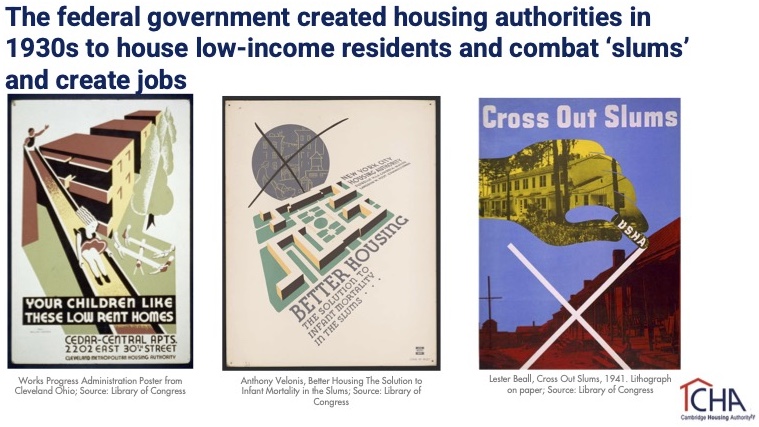

As a historical reminder, housing agencies in the United States were created by the federal government in the 1930s, in response to the Great Depression. As part of the New Deal’s wide range of programs, the Public Works Administration helped launch the first large-scale public housing program in the United States—comparable in intent to social housing in some European countries.

The programme aimed to create jobs and provide affordable housing for the urban poor, with the assumption that rents would cover costs and that local agencies would manage the projects.

Unfortunately, many ensembles were segregated — a problem that lasted until the 1980s.

When I first joined the Housing Authority, it was clear that some buildings were geared towards specific racial groups.

The Public Works Administration resulted in the U.S. Housing Act of 1937, which is still a pillar of housing policy today. This law transferred to local authorities the responsibility for subsidies to build and manage federal public housing.

The program has grown significantly: at its peak, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, it had about 1.4 million units managed by nearly 3,300 housing agencies of various sizes.

However, federal policies have imposed significant constraints. Every housing agency is created under state law, not federal law, and state regulations can conflict with federal rules, leading to inefficiencies, extra costs, and confusion. Early policies often required that every new housing unit built result in the demolition of an existing substandard dwelling; Public housing thus tended to replace the existing stock rather than to increase it, sometimes destroying dynamic immigrant neighbourhoods without any real integration with the neighbouring urban fabric. Federal rules also imposed strict caps on construction costs, leading to low-quality buildings, shortcuts in design and construction, and high long-term maintenance costs.

The program then shifted from cost-covering rents to income-geared rents, targeting households with very low resources. This change resulted in insufficient rental income to cover operating costs, making housing agencies increasingly dependent on federal subsidies. Over time, these factors—poor design, underfunding, and political shifts—turned public opinion and political support against public housing, beginning in the 1970s and 1980s. Funding has been frozen and then reduced; Policies have encouraged privatization through rent subsidies and tax credits, attracting private investment but turning affordable housing into a commodity, which has increased costs and sometimes reduced real affordability. As a result, the national public housing stock has fallen from about 1.4 million units in the early 1990s to less than 900,000 today — about 500,000 homes lost in 25 to 30 years.

This evolution left the responsibility of defining their own housing policies to the States and then to the cities. Cambridge is a relatively old and dense American city — about 18,500 people per square mile, making it the 25th densest city in the country — and it adjoins Boston across the river. The proximity of Boston has benefited Cambridge, as Boston absorbs some of the needs of vulnerable populations. Cambridge is home to two world-class universities as well as many technology and biotech companies, making it a city of high opportunities and resources that enhance life trajectories.

Cambridge is very walkable and embodies many of the characteristics of the “quarter of an hour city”: it is small and compact, with food shops, schools, health services, parks and jobs within walking or cycling distance. Many of the Cambridge Housing Authority’s units are integrated into this accessible urban fabric.

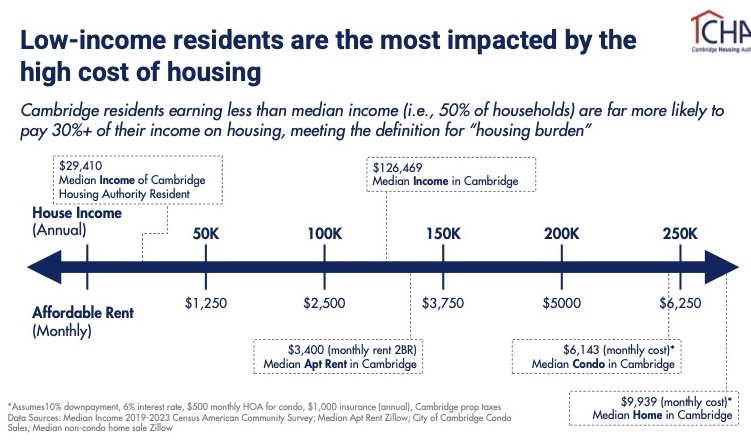

But with this attractiveness comes extremely high living costs, especially for housing, a trend that has worsened over the past twenty to thirty years. High housing costs are a major barrier to accessibility for people who work in the city but cannot afford housing — especially low- and middle-income households supported by the Housing Authority.

In my more than thirty years of experience, many long-time residents have been forced to leave, and the character of neighborhoods has changed dramatically.

Employment growth in the Cambridge–Boston region has been strong, but housing supply has not kept pace. Housing costs in Cambridge are much higher than the national average, and almost half of renters are in financial overload, spending more than 30% of their income on housing. For example, the median income of Cambridge residents is just under $30,000 per year, which would allow, according to the 30% rule, to pay about $735 in monthly rent. However, the median rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Cambridge is around $3,400 — nearly five times what the median resident can afford. Even workers earning $50,000 to $60,000 a year could only bear about $1,400 in rent under this rule, well below market prices. This problem is not limited to Cambridge; it concerns the entire Boston metropolitan area and beyond. Some Housing Authority agents take more than two hours to get to work because of a lack of affordable housing nearby.

Responsibility has been gradually shifted from the federal government to the states and then to the cities, with each level having different policies and constraints, making it difficult to produce affordable housing effectively. Cambridge, however, has taken proactive steps in recent years to increase housing production and diversity. The city established an Affordable Housing Trust Fund in 1989, which today funds more than $60 million annually. Cambridge implemented inclusive zoning early on, requiring that approximately 20% of housing in eligible private projects be affordable. Five years ago, the city introduced an affordable housing overlay, allowing high heights and densities for 100% affordable projects in its own right — a major benefit for the Housing Authority. Parking obligations have been abolished in order to increase the number of buildable housing units and the sites available. About a year ago, Cambridge adopted citywide multi-family zoning, allowing apartment buildings in all neighborhoods — whereas previously half of the city was limited to two- or three-unit homes. This zoning now allows, as of right, four-storey buildings, or even six storeys in certain sectors, with relaxed rules in terms of setbacks and land use coefficients. These changes facilitate the production of housing, both affordable and private.

What sets the Cambridge Housing Authority apart is based on four main elements.

First, our desire to innovate and strive for excellence. Fifty years ago, the agency was badly managed and close to being placed under supervision by the State or the courts; Since then, management and teams have established a culture of excellence, innovation and partnership with residents and the City.

Second, we have adopted a great deal of financial flexibility through the federal Moving to Workprogram, created by Congress in the late 1990s, which allows certain agencies, including ours, to pool different sources of funding and use them where the impact is greatest, by adapting rent policies locally. services and even development.

Thirdly, we have invested in the skills of the public sector: our teams are not limited to management and maintenance, but also provide financing, development and monitoring of construction sites – which is unusual for many agencies. This allows us to control quality and generate revenue to fund new programs.

Fourth, we have expanded our work beyond the built environment to include programs that improve the quality of life of residents and break the intergenerational reproduction of poverty, including certification training in property management and programs for young people, promoting social mobility and home care with dignity.

Moving forward, we need to continue to evolve to stay relevant. We are expanding the income levels of the people we serve — by helping people experiencing homelessness and experimenting with mixed-income housing programs. We are developing regional partnerships with other agencies in Massachusetts because the Cambridge challenges are regional in scale. We are also acquiring buildings and land: we finalised the purchase of one property at the end of December and plan to conclude five more. We hope to increase our stock by more than 20% over the next five years and by nearly 40% over ten years, in line with the city’s objective of adding 12,500 housing units — an increase of 20% — in five years.

The issue of homelessness

Over the past five years, especially since the pandemic, we have focused heavily on homelessness. The pandemic has highlighted how much the place of life influences survival; People in precarious residential situations or without housing have been disproportionately affected. We have adopted models of supported housing, combining housing and services. Recently, we renovated or acquired housing to directly accommodate people living on the street, by accompanying them with services that facilitate the transition and take into account health and behavioural issues. This approach has proven to be effective.

Beyond directly managed supported housing, we work with frontline organizations by providing them with rent subsidies and operating subsidies, especially for survivors of domestic or sexual violence, young people leaving child welfare, and other groups in need of emergency housing. These programs have shown their effectiveness.

-oOo-